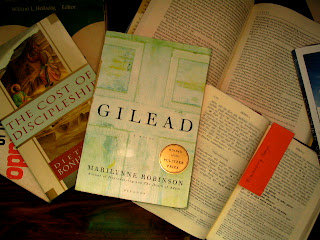

Today my cohort-mates sit down to lectures on the Holiness Code, the emergence of endowed preacherships in the years leading up to the Reformation, and C5 contextualization. Today I sit down in my reading chair to peruse a long-neglected stack of novels. I have to wonder who's getting the better ministerial education.

Marilynne Robinson's Gilead presses this question dearly. Gilead is comprised of the letters of an old an dying minister to the son he fathered very late in life. Karl Barth and Ludwig Feuerbach appear in these pages. So do sermon notes, scripture citations, Abraham, Job, Paul, Jesus. I'll admit, I'm jealous of the theological education of the Reverend John Ames; perhaps my own alma mater could have done with a bit more attention to a few German theologians.

But one ought not read Gilead simply for its theological performance. Read the novel for the way it unveils the world--the tragic world--as beautiful.

The book is shot through with tragedy: goodbyes never said, relationships never healed, the past buried in back by a fencepost, the future miscarried or foreclosed on by by ill-timing. Tragedy everywhere, even, I suppose, in too much seminary education (as is the case with Ames' brother Edward). Tragedy fills the pages of this book the way that it fills the space between the atoms that make up daily life.

But if one will just walk slow or sit with one's eyes open, if one looks deeply enough, beauty appears to be intimately wed to tragedy, making a home just as deep in reality as pain and evil. The letters that one-by-one carry this story read like letters, like journal entries. They sit and they look, absorbed and yet fully self-conscious, a patient self-narration of experience that never forgets itself while yet allowing itself to be caught up in the other. John Ames' letters reveal perceiving beauty and patient attention walk hand-in-hand.

Take this recollection, for instance:

That mention of Feuerbach and joy reminded me of something I saw early one morning a few years ago, as I was walking up to the church. There was a young couple strolling along half a block ahead of me. The sun had come up brilliantly after a heavy rain, and the trees were glistening and very wet. On some impulse, plain exuberance, I suppose, the fellow jumped up and caught hold of a branch, and a storm of luminous water came pouring down on the two of them, and they laughed and took off running, the girl sweeping water off her hair and her dress as if she were a little bit disgusted, but she wasn't. It was a beautiful thing to see, like something from a myth. I don't know why I I though of that now, except perhaps because it is easy to believe in such moments that water was made primarily for blessing, and only secondarily for growing vegetables or doing the wash. I wish I had paid more attention to it. My list of regrets may seem unusual, but who can know that they are, really. This is an interesting planet. It deserves all the attention you can give it.Now listen to how he follows it in the next paragraph:

In writing this, I notice the care it costs me not to use certain words more than I ought to. I am thinking about the word "just." I almost wish I could have written that the sun just shone and the tree just glistened, and the water just poured out of it and the girl just laughed--when it's used that way it does indicate a stress on the word that follows it, and also a particular pitch of the voice. People talk that way when they want to call attention to a thing existing in excess of itself, so to speak, a sort of purity or lavishness, at any rate something ordinary in kind but exceptional in degree. So it seems to me at the moment. There is something real signified by the word "just" that proper language won't acknowledge. It's a little like the German ge-. I regret that I must deprive myself of it. I takes half the point out of telling the story.This "existing in excess of itself"--this is the mode of beauty in real life. The Reverend John Ames stumbles on it, and I think Robinson weaves her novel to run us headlong into it. For how else can the truly tragic--death, violence, heartbreak, sickness, hunger, old age, lies, deceit and the like--be also truly beautiful, if not in excess of its natural existence. Tragedy is "ordinary in kind"; beauty is certain way of being "exceptional in degree."

To read Gilead, you must be a patient reader--at least if you are to realize its beauty. It's story sits so unobtrusively in the ordinariness of the room, waiting on the sofa so comfortably that you'd think it too was just one more piece of furniture, not a guest from out of town or a prodigal returned home. And even after you realize who this guest is, the story feel familiar, like a joke you've heard before or a newspaper clipping you've just rediscovered in the recesses of your desk. Patience reveals the ordinary.

Patience reveals the ordinary as unexpected, and vice versa. Living in place, waking to the same stretches of ranch land or concrete or beach, you slowly become habituated to the foreigness of your day-to-day experience. I found this true when I lived for seven months in Skopje, Macedonia. After only a few weeks the sour smell of garbage, the acrid sting of wood smoke, and the ever present diesel fumes ceased to register in my mind. The looming Millennium Cross atop Mount Vodno seemed natural. The Cyrillic shop signs made more or less sense. The hustle from house to market to Bible study to school back to home kept my sense too busy processing to allow for perception. But when I'd stop in a kafich for a cup of tursko kafe, or when I'd stand waiting for my bus to come to the station, once in a while the beauty, the otherness and yet also the familiarity of my surrounding would register, and I would rejoice in the chance to be here doing precisely what I was doing. (Like John Ames, I often found paper and pen helped this deeper processing.)

In college, my wife had a quote posted somewhere on her desk that said something like "A writer is first and foremost a fierce observer of the world." I am beginning to feel that this should also be true of a Christian. If Jesus is the wisdom--what perhaps we should better translate today beauty--of the world, then we must commit ourselves to finding him, his ordering work, everywhere. Especially in tragedy.

Listen to another (sizable) passage from Gilead, this time from Ames' recollection of the conclusion of a childhood pilgrimage:

When we finished, my father sat down on the ground beside his father's grave. He stayed there for a good while, plucking at little whiskers of straw that still remained on it, fanning himself with his hat. I think he regretted that there was nothing more for him to do. Finally he got up and brushed himself off, and we stood there together with our miserable clothes all damp and our hands all dirty from the work, and the first crickets rasping and the flies really beginning to bother and the birds crying out the way they do when they're not about ready to settle for the night, and my father bowed his head and began to pray, remembering his father to the Lord, and also asking the Lord's pardon, and his father's as well. I missed my grandfather mightily, and I felt the need of pardon, too. But that was a very long prayer.

Every prayer seemed long to me at that age, and I was truly bone tired. I tried to keep my eyes closed, but after a while I had to look around a little. And this is something I remember very well. At first I thought I saw the sun setting in the east; I knew where east was, because the sun was just over the horizon when we got there that morning. Then I realized that what I saw was a full moon rising just as the sun was going down. Each of them was standing on its edge, with the most wonderful light between them. It seemed as if you could touch it, as if there were palpable currents of light passing back and forth, or as if there were great taut skeins of light suspended between them. I wanted my father to see it, but I knew I'd have to startle him out of his prayer, and I wanted to do it the best way, so I took his hand and kissed it. And then I said, "Look at the moon." And he did. We just stood there until the sun was down and the moon was up. They seemed to float on the horizon for quite a long time, I suppose because they were both so bright you couldn't get a clear look at them. And that grave, and my father and I, were exactly between them, which seemed amazing to me at the time, since I hadn't given much thought to the nature of the horizon.

My father said, "I would never have thought this place could be beautiful. I'm glad to know that."Beauty, tragedy, patience. When I'd first finished Gilead, I thought of it as a narrative meditation on Luke's parable about the prodigal son, but now I think I was wrong. If the story must be about something, I think it is about baptism. In baptism, what is utterly ordinary is revealed to put together out of millions of millions of shards of the extraordinary. An ordinary life, in all its boredom and tragedy, is shown to be wholly, entirely holy, loved of God, existing in a new creation. Somehow, this cuts both ways.

A final quote:

Ludwig Feuerbach says a wonderful thing about baptism. I have it marked. He says, "Water is the purest, clearest of liquids; in virtue of this its natural character it is the image of the spotless nature of the Divine Spirit. In short, water has a significance in itself, as water; it is on account of its natural quality that it is consecrated and selected as the vehicle of the Holy Spirt. So far there lies at the foundation of Baptism a beautiful, profound natural significance." Feuerbach is a famous atheist, but his about as good on the joyful aspects of religion as anybody, and he love the world.

Thanks for this great review, Josh! (And congrats on finishing coursework!) Cindy recommended this book to me around New Years and I'm still working through it. It feels like such a testimony of Midwestern heritage to me: wisdom from the honest life our American forebears led in the face of harsh circumstances. You pointed out some of my favorite passages too!

ReplyDelete